By way of background, a classmate of mine from undergrad has been holding Oscar parties for over 25 years. As part of this Oscar party, he's also held a guess-the-winners contest. With between 50 and 100 contest entries annually for most of the period, that's a lot of ballots. And, being Steve, he's carefully saved and organized all that data.

Over the years, we've chatted about various aspects of the results, observed some patterns, and wondered about others. For example, has the widespread availability of Oscar predictions from all sorts of sources on the Internet changed the scores in this contest? (Maybe. I'll get to that.) After the party this year, I decided to look at the historical results a bit more systematically. Steve was kind enough to send me a spreadsheet with the lifetime results and follow up with some additional historical data.

I think you'll find the results interesting.

But, first, let's talk about the data set. The first annual contest was in 1987 and there have been 1,736 ballots over the years with an average of 67 annually; the number of ballots has always been in the double-digits. While the categories on the ballot and some of the scoring details have been tweaked over the years, the maximum score has always been 40 (different categories are worth different numbers of points). There's a cash pool, although that has been made optional in recent years. Votes are generally independent and secret although, of course, there's nothing to keep family members and others from cooperating on their ballots if they choose to do so.

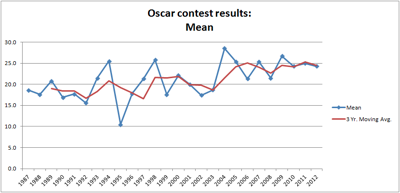

The first thing I looked at was whether there were any trends in the overall results. The first figure shows the mean scores from each year graphed in a time series, as well as a three-year moving average of that data. I'll be mostly sticking to three-year moving averages from hereon out as it seems to do a nice job of smoothing data that is otherwise pretty spiky, making it hard to discern patterns. (Some Oscar years bring more upsets/surprises than others, causing scores to bounce around quite a bit.)

Is there a trend? There does seem to be a slight permanent uptick in the 2000s, which is right where you'd expect there to be an uptick if widespread availability of information on the Internet were a factor. That said, the effect is slight. And running the data through the exponential smoothing function in StatPlus didn't turn up a statistically significant trend for the time series as a whole. (Which represents the sum total of statistical analysis applied to any of this data.) As we'll get to, there are a couple other things that suggest something is a bit different in the 2000s relative to the 1990s, but it's neither a big nor indisputable effect.

Color me a bit surprised on this one. I knew there wasn't going to be a huge effect but I expected to see a clearer indication given how much (supposedly) informed commentary is now widely available on the Internet compared to flipping through your local newspaper or TV Guide in the mid-nineties.

We'll return to the topic of trends but, for now, let's turn to something that's far less ambiguous. And that's the consistent "skill" of Consensus. Who is Consensus? Well, Consensus is a virtual contest entrant who, each year, looks through all the ballots and, for each category, marks its ballot based on the most common choice made by each of the human contest entrants. If 40 people voted for The Artist, 20 for Hugo, and 10 for The Descendants for Best Picture, Consensus would put a virtual tick next to The Artist. (Midnight in Paris deserved to win but I digress.) And so forth for the other categories. Consensus then gets scored just like a human-created ballot.

As you can see, Consensus does not usually win. But it comes close.

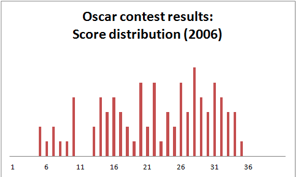

And Consensus consistently beats the mean, which is to say the average total score for all the human-created ballots. Apparently, taking the consensus of individual predictions is more effective than averaging overall results. One reason is that Consensus tends to exclude the effect of individual picks that are, shall we say, "unlikely to win." Whereas ballots seemingly created using a dartboard still get counted in the mean and thereby drive it down. If you look at the histogram for 2006 results, you'll see there are a lot of ballots scattered all over. Consensus tends to minimize the effect of the low-end outliers.

But how good is Consensus as a prediction mechanism compared to more sophisticated alternatives?

We've already seen that it doesn't usually win. While true, this isn't a very interesting observation if we're trying to figure out the best way to make predictions. We can't know a given year's winner ahead of time.

But we can choose experts in various ways. Surely, they can beat a naive Consensus that includes the effects of ballots from small children and others who may get scores down in the single digits.

For the first expert panel, I picked those with the top five highest average scores from among entrants in at least four of the first five contests. I then took the average of those five during each year and penciled it in as the result of the expert panel. It would have been interesting to also see the Consensus of that panel but that would require reworking the original raw data from the ballots themselves. Because of how the process works, my guess that that this would be higher than the panel mean but probably not much higher.

For the second panel, I just took the people with the 25 highest scores from among those who had entered the contest for at least 20 years. This is a bit of a cheat in that, unlike the first panel, it's retrospective--that is, it requires you in 1987 to know who is going to have the best track record by the time 2012 rolls around. However, as it turns out, the two panels post almost exactly the same scores. So, there doesn't seem much point in overly fussing with the panel composition. Whatever I do, even if it involves some prescience, ends up at about the same place.

So now we have a couple of panels of proven experts. How did they do? Not bad.

But they didn't beat Consensus.

To be sure, the trend lines do seem to be getting closer over time. I suspect, apropos the earlier discussion about trends over time, we're seeing that carefully-considered predictions are increasingly informed by the general online wisdom. The result is that Consensus in the contest starts to closely parallel the wisdom of the Internet because that's the source so many people entering the contest use. And those people who do the best in the contest over time? They lean heavily on the same sources of information too. There's increasingly a sort of universal meta-consensus from which no one seriously trying to optimize their score can afford to stray too far.

It's hard to prove any of this though. (And the first few years of the contest are something of an outlier compared to most of the 1990s. While I can imagine various things, no particularly good theory comes to mind.)

Let me just throw out one last morsel of data. Even if we retrospectively pick the most successful contest entrants over time, Consensus still comes out on top. Against a Consensus average of 30.5 over the life of the contest, the best >20 year contestant scored 28.4. If we broaden the population to include those who have entered the contest for at least 5 years, one person scored a 31--but this over the last nine year period when Consensus averaged 33.

In short, it's impossible to even beat Consensus consistently by matching it against a person or persons who we know with the benefit of hindsight to be the very best at predicting the winners. We might improve results by taking the consensus of a subset of contestants with a proven track record. It's possible that experts coming up with answers cooperatively would improve results as well. But even the simplest and uncontrolled Consensus does darn well.

This presentation from Yahoo Research goes into a fair amount of depth about different approaches to crowdsourced predictions as this sort of technique is trendily called these days. It seems to be quite an effective technique for certain types of predictions. When Steve Meretzky, who provided me with this data, and I were in MIT's Lecture Series Committee, the group had a contest each term to guess attendance at our movies. (Despite the name, LSC was and is primarily a film group.) There too, the consensus prediction consistently scored well.

I'd be interested in better understanding when this technique works well and when it doesn't. Presumably, a critical mass of the pool making the prediction needs some insight into the question at hand, whether based on their own personal knowledge or by aggregating information from elsewhere. If everyone in the pool is just guessing randomly, the consensus of those results isn't going to magically add new information. And, of course, there are going to be many situations where data-driven decisions are going to beat human intuition, however it's aggregated.

But we do know that Consensus is extremely effective for at least certain types of prediction. Of which this is a good example.

2 comments:

My impression here is that you're looking at data that comes from people who often fill it out at the last minute or haphazardly. On the web, not that many sites go into the "minor awards" and the Academy itself often messes everyone up by not going for the internet consensus favorite.

@DaveL It's a mix. I can assure you that there is a core group of people here who do indeed take this contest pretty seriously. There are others, of course, who do not.

Post a Comment